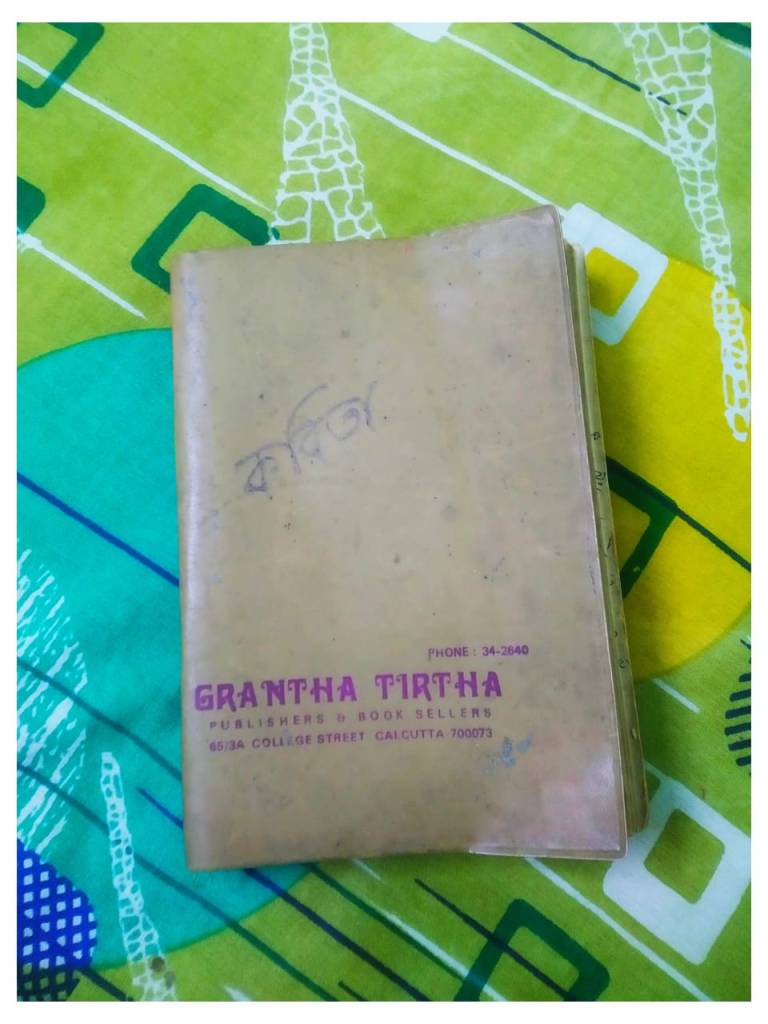

A few days ago, I found a diary – an old, yellowish little diary. At first, it was difficult for me to recognize to whom it belonged – me, my sister, my father, or my mother. But when I took it in my hand, I recalled it was my Dadu’s diary of poems, which I had seen once in my childhood, and then it was lost in the heap of old books and diaries and stayed away from my notice.

I quietly brought that diary to my room and kept it in my closet secretly, hiding from the curious eyes around me. I decided to read it alone, locking my room, in some quiet moment, to ponder upon my Dadu’s poems.

It took me a few weeks to get that ‘quiet moment’. No, it wasn’t completely quiet; I was having restlessness within, so there was chaos in my mind and thumping beats in my heart, when I finally brought the diary out of my closet and started reading.

As I opened the first page, I saw it was written there:

1st Part: These poems I wrote for children. I had a wish to publish a children’s poems book one day, and then sell the book in our bookstore. It didn’t happen, but I wanted to keep them here with all my love and affection.

The words written on the first page of the diary made me teary-eyed. I sobbed and re-read the same page countless times. For the next half an hour, I was reading the same words, the same lines, again and again, and crying silently.

What made me read the same thing repeatedly? My Dadu’s unfulfilled wish.

A lot of emotions engulfed me; I was feeling sad and guilty for not being able to fulfill my Dadu’s wish yet, but on the other hand, I was feeling happy that I found the diary once again, I was feeling proud of my choice of career that I was following my Dadu’s abandoned path of being a ‘Writer’. Most importantly, I was feeling excited to have found my Dadu’s poetry collection, and in the bottom of my heart, a secret wish blossomed that one day, I would publish and sell my Dadu’s poetry collection.

Then, slowly, I allowed myself to proceed. Flipping through the pages, I read the poems – the sweet, innocent, and childish poems. The moment I was wondering about the idea of publishing my Dadu’s work in the future, I had another revelation.

As I proceeded further with my reading, I came across the 2nd Part, which was a collection of his ‘Ramya Kabita’ or sarcastic poems.

After some pages, I reached where it was written:

3rd Part: Poems for grown-ups (I wrote these poems in the entire span of my life until the day my pen stopped.)

Most of his poems included in the 2nd and 3rd parts of the collection were retrieved from the dusty, yellowish papers, waiting to be sold to the raddiwallah. Fortunately, before going to the raddiwallah, Dadu wanted to check if there were any important papers mistakenly placed in the heap of papers gathered, and there, he found these jewels bundled.

It was a breakthrough discovery for me when I read the poems written in the 2nd and 3rd parts of the diary. The poems were a collection of wise words from a publicly atheist but privately spiritual person.

I discovered a new identity of my Dadu through his poems, as they were like a mirror to the person whom we never knew completely.

Reading the children’s poems, I realized why he was keen to teach me to write poetry. He started his teaching when I was nine years old. He was often addressed as ‘The Royal Bengal Tiger’ of the house by my uncle and other young family members. He wore that personality throughout his whole lifetime. But inside him was hiding a child who might have lost his childhood very early due to the circumstances and consequences of the Indian Independence Movement, the Bengal Partition, and the Communal Riots in the post-partition period. Therefore, he wanted to keep his inner child alive in the children’s poems he wrote.

Next, I had a strange realization about his faith in God. I never saw him pray, burn the incense sticks, chant a mantra, or even enter the temple of the house. On the occasions of Janmashtami or Durga Puja, or Diwali, when we all went to the temples of the town and worshipped the deities, he stayed alone in the house. Though he didn’t forbid anyone from nurturing their own beliefs, we knew that he had been an atheist for his entire life.

But what about the poems that read like worshipping mankind through cultivating kindness?

I learned from his poems that he always believed in the Omnipresence but never had faith in performing the rituals. Pretty obvious from a person like him, who witnessed the cruelty of society and faced the challenges of life at a very young age. He might lose his faith in God, but never denied his belief in the presence of the Divine Power, and thus, he did his ‘offerings’ through his poems.

The next thing that made me astonished was learning the writing prowess of my Dadu and his inclination towards pondering societal norms and expressing his own thoughts and opinions about them through his poems. Especially, Dadu wrote hugely on the topic of ‘Hunger’ and ‘Poverty’ that made me bow in awe.

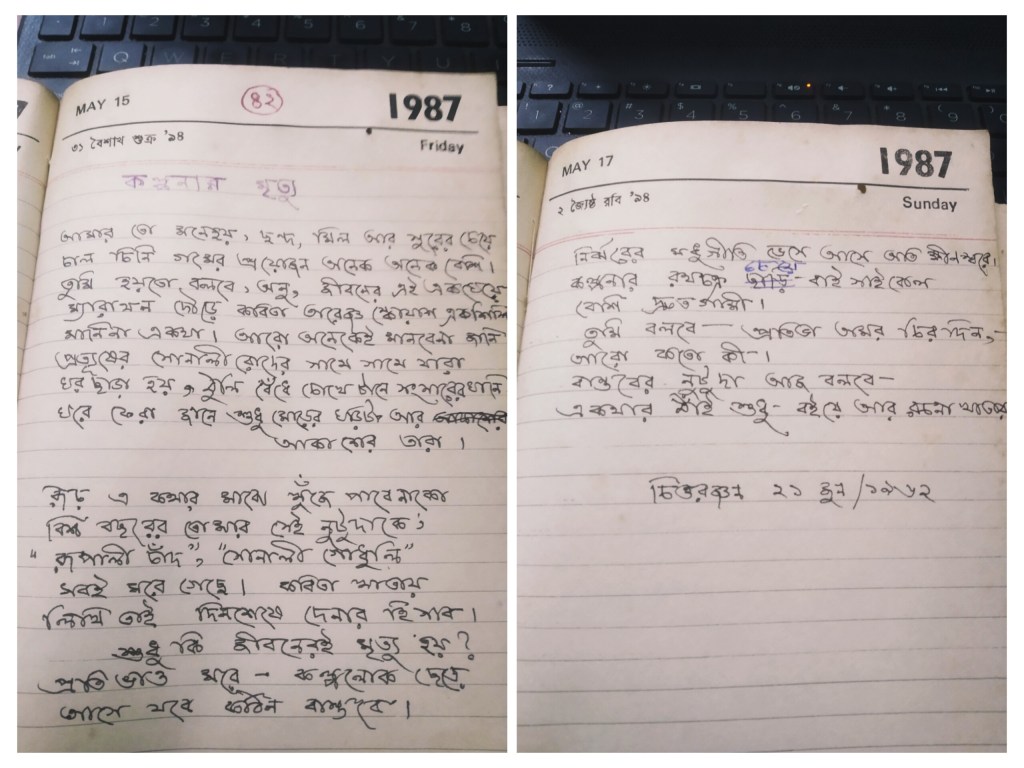

But the topic that made me pause longest and ponder deepest was the necessity of writing poetry. He often wrote about the importance of poetry to an ordinary man who is burdened with the responsibility of running a household with his wife and raising their five children. He tried hard to keep the poet in him alive, but the promise to his family couldn’t make him write his heart out.

He mentioned in his poems how his notebook’s pages, where he planned to write his poetry, were filled with the daily calculations of expenditures and savings. He created two characters named ‘Anu’ and ‘Nutu Da’. Anu, being an anonymous reader and a fan of his poetry, and ‘Nutu Da’, an ordinary man, once a poet, now a salaried person, yet dealing with the dilemma between the promise he made to Anu to continue writing poetry, and the responsibilities for the survival of seven lives.

In continuation of the same theme, I read another poem, written thirty years later. In this poem, Dadu, now a retired person, regrets not being able to write anything. When he was busy with his duties, he had so many things to write, maybe in the form of a poem or a book, but now, he has nothing left to give his messy thoughts the desired shape.

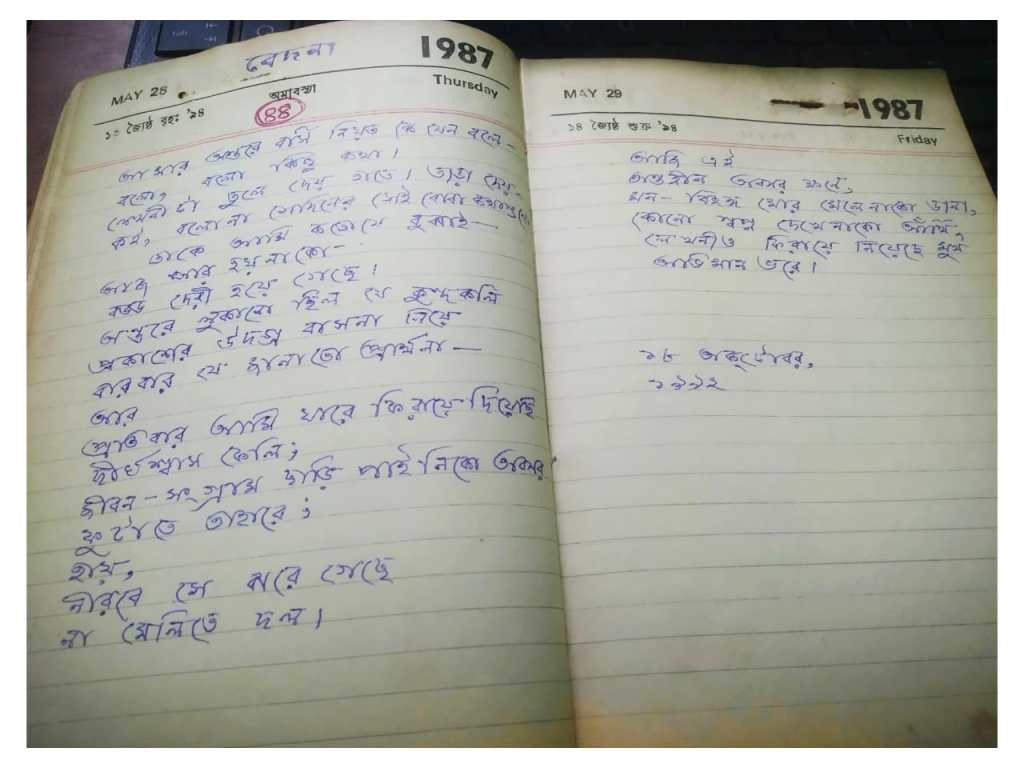

After reading the poem titled ‘Bedona’, I pondered for the longest period. The poem narrates the silent pain of a poet in his sixties who, after a long hiatus, discovered that he had forgotten how to write. Before taking farewell from his writing journey, he wrote his last poem.

Here is the English translation of ‘Bedona’ by me:

The Pain of a Poet

A voice I hear,

As if someone sitting in my heart

Sends his whisper to me,

“Say, say something.”

Giving me the quill, he tells me,

“Time is running,

You have so many words unsaid,

This is the hour,

Write down everything that you buried in silence.”

I try to make him understand

That now I can’t write –

It’s too late.

In my youth,

I was carrying a prayer within,

My words wanted to bloom like the star jasmine.

But at that time, I didn’t allow them to blossom,

With a sigh, I refused them over and over;

Heartbroken, they left without receiving any offering from me.

Being occupied in the struggle of life,

I couldn’t get time

To pursue my love for poetry;

I couldn’t unfurl the petals –

I saw the fallen buds. On the ground

As they left their hope to become a flower.

Now, as I am retired from my job

I have ample time doing nothing.

But the bird of my heart forgot to stretch his feathers now,

My eyes have stopped dreaming,

Hiding the pain in silence

My quill has also refused me,

And I am left all alone

With the unsaid words I have been carrying within.

– Haripada Nath, Chittaranjan, 18th October, 1992

Doesn’t this pain echo to all the poets? Don’t we, the poets, share the same pain? No matter what’s been written so far, we may have a lot more unsaid, buried within silence. For we know, silence writes the most beautiful poetry.

___________________________________________________________________________________

(“This post is a part of ‘Verse Wave Blog Hop’ hosted by Manali Desai and Sukaina Majeed under #EveryConversationMatters”)

(This post is also a part of the #BlogchatterBlogHop powered by Blogchatter.)

Leave a reply to Swarnali Nath Cancel reply